Hicock-Benson-Palmer (HBP) Site

The Hicock-Benson-Palmer site is located near Transylvania Brook in Southbury, CT. Sometimes (and in the case of the HBP site) archaeologists are not the first to arrive at an archaeological site. Because of this, regulations have been put in place to protect areas that are considered at “high risk” for disturbance. Unfortunately, these regulations can often be ignored, difficult to enforce, or may be situationally limiting. The effects of these circumstances can be detrimental to a site’s integrity and severe cases can result in permanent loss of valuable information. Salvage archaeology attempts to determine a site’s archaeological significance before their context is disrupted. Commercial developments, infrastructural construction, looting, and flooding are all threats that can warrant a salvage archaeological survey.

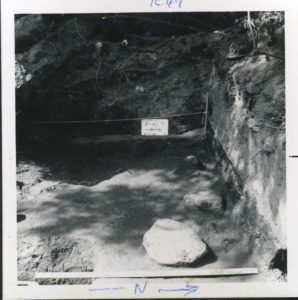

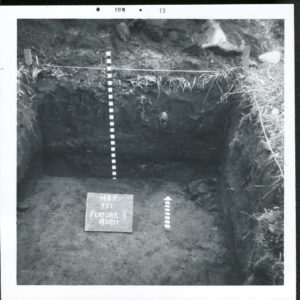

A land-clearing project was already underway at the HBP site when its potential historical significance was brought to the attention of Edmund Swigart, co-founder of both the Institute for American Indian Studies and the Shepaug Valley Archaeological Society. To avoid further damage to the site, Swigart mobilized a group of volunteers to conduct a salvage excavation as quickly as possible. Despite heavy disturbance in a large area of the HBP site, they were able to recover thousands of artifacts and cultural features that reflected small Terminal Archaic/Middle Woodland components and an extremely robust 14th century Late Woodland component. Analyses of floral and faunal remains determined that this occupation represents a multi-seasonal settlement. For instance, based on seasonal availability, wild cherry pits found in this context place it in late June/July, and hickory and walnut remains point to September/November. Additionally, the presence of fawn bone reinforces these temporal identifications based on local deer breeding patterns.

This assemblage was also able to provide insight on the social composition of the Late Woodland group as well as the various activities they may have engaged in. The relatively large number of hearths suggest that it was composed of multiple families and the diverse array of ceramic styles prove that these groups returned to the area for many years. It is evident that stone tool manufacturing was a primary activity here due to the presence of thousands of stone flakes and other lithic debitage. By analyzing HBP’s ceramic assemblage, Dr. Lucianne Lavinia discovered that this Late Woodland community had strong social connections to surrounding groups. The variability of pot rim shapes, decorative techniques, and treatment among these vessels mirrors contemporary assemblages along the Connecticut coast and the Hudson River Valley. It is clear that the people at HBP and these areas were in contact with each other, most likely through trade, and influenced each other’s ceramic practices.

It is also important to note what was not found at the HBP site. For instance, there was not evidence of maize, bean, or sunflower consumption, which is a stark deviation from other sites of this time period and region. Located near both a river and quartz quarry, this area would have been an advantageous spot to occupy. Unfortunately, the destruction of a large portion of the site prior to the arrival of archaeologists caused an unknown extent of damage. Thanks to the efforts of Edmund Swigart and his volunteers, many artifacts and cultural features were preserved and were able to provide information on Late Woodland period settlements in this region.

Citations

Lucianne Lavin

2008 The Hicock-Benson-Palmer Site: A Significant Later Woodland Living Site in South Britain. The Birdstone Newsletter Vol. 7, No.1. Published by the Institute for American Indian Studies.

Jacob Orcutt

2014 Hicock-Benson-Palmer (6NH109) Site and the Hicock Hensel Cave. Unpublished Intern Report.